Introduction

We now know that almost every star has a planet, and our Earth, or even life, may not be special in the universe. We want to understand how our Earth and other Earth-like planets formed billions of years ago. Although the planetary nursery, or protoplanetary disk, is long gone in our own Solar System, similar planetary nurseries still exist in other young stellar systems in the universe. Unfortunately, these systems are difficult to study since they are faint and far away. Only within the past several years, telescopes are powerful enough to resolve the planetary construction zone in these disks for the first time. A large amount of observational data has poured in recently, but little information can be extracted from these data without detailed theoretical modeling. We are constructing theoretical models to compare with these observations, with the final goal of understanding the planet formation process.

Accretion and Structure

Protoplanetary disks are important for both star and planet formation. The star can grow its mass by accreting the disk material, while planets are directly born in this disk. The disk accretion is driven by turbulence within the disk and/or large scale magnetic fields threading through the disk. We study hydrodynamical, magnetohydrodynamical and radiation processes in the disk by carrying out large-scale numerical simulations. We use various numerical codes, including the Pencil code and Athena++.

Planet-Disk Interactions

When young planets emerge in the protoplanetary disk, they will interact with the disk. This interaction is important for planet evolution and planet detection. Due to the interaction, the planet can continue to grow its mass (moons can also form around the planet) and migrate in the disk. The interaction can also produce observable signatures such as spiral arms and gaps in protoplanetary disks, which provide the observational signatures of young planets in protoplanetary disks.

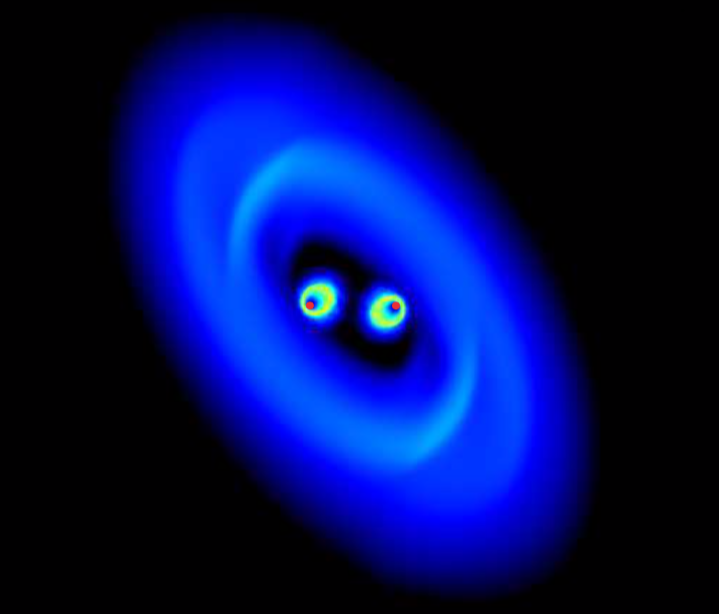

Binary Companions

Most stars are in binary star systems rather than being single stars like our Sun. Protoplanetary disks can form around each separate component of a wide binary but also around both components of a close binary. These are known as circumbinary disks and they may also be a site for planet formation. Indeed, around 20 circumbinary planets have been found so far. Circumbinary planets are much more difficult to detect than planets that orbit around a single star. Inner and outer binary components can have a significant impact on the dynamics and evolution of a protoplanetary disk and the planets that may form in the disk. In order to explain the observed properties of exoplanets, we need to understand the impact of binary companions.